Market Research For More Effective Ad Campaigns

Decisions related to advertising remain an essential part of the life science marketer’s responsibilities. He or she is required to select the right medium, form and frequency for advertising contacts with existing and potential customers across a wide range of market segments and scientific disciplines. Advertising is as expensive as it is important, and the costs of launching an ill-conceived campaign can be higher than not advertising at all. At BioInformatics Inc. we have conducted advertising research for many companies (and their agencies) to understand market segmentation and media preferences as well as testing designs, images and messaging. We’ve pulled together a few examples of how are qualitative and quantitative approached to advertising research that can be downloaded here. This article discusses some of my observations about advertising in the life science tools market and why I believe advertising research is a critical component to a successful campaign.

The greatest difficulty facing the manager responsible for formulating and executing an advertising campaign is the lack of consensus within the company on an ad’s purpose and ultimate value. When various constituencies within a company have different goals and expectations, the resulting message of the campaign is equally confusing to customers. At some levels within the company, advertising is expected to change customer perceptions, maintain awareness, reinforce brand loyalty, capture new customers and prompt a flurry of purchasing activity. Others (notably those with a creative flair) want advertising to entertain, intrigue, please or amuse the targeted scientific customer. Such a broad spectrum of goals makes it difficult to derive a consistent set of objectives that can be accepted by all interests within the company—corporate management, R&D, marketing and sales.

Another area of confusion prevalent in most companies is the timeframe for measuring effectiveness. Some executives within a company believe advertising should be used to influence sales in near-real time, while others view it as a long-term investment in building a brand identity over many months or even years. This disconnect between what advertising is intended to achieve permeates all decisions related to the campaign and leads to confusing or contradictory messages that fail to either inform or influence the targeted market.

Without a consensus as to what the advertising is intended to achieve, it is impossible to set clear objectives. Furthermore, without clear objectives, measuring the success of the ad can become problematic. And measuring success must be more broadly defined than simply countin impressions and clicks. Unfortunately, the high visibility of advertising decisions tends to make decision-makers shy away from measuring advertising effectiveness beyond digital analytics and instead, articulate their goals in an ambiguous manner.

If a company cannot demonstrate that the money it spends on advertising generates revenue by informing customers and influencing their purchases, the company should consider abandoning advertising all together. On the other hand, if clear objectives are set, progress toward meeting those objectives can be measured. If progress can be measured, the same company may well find they are not spending enough on advertising, or, they may find that those dollars being spent are not being put toward the right kind of advertising.

All those responsible for advertising must be held more accountable for the results of a campaign. Too often, managers find themselves seduced by the more glamorous aspects of advertising and forget that their mission is to inform and influence customers—not win awards for their agency. After an initial period of uncertainty and organizational resistance, the results of analyzing ad performance will lead to greater confidence in spending decisions—whether they are eventually higher or lower. Most significantly, measures of accountability tend to make creative and placement decisions more rational and ultimately more successful.

Determining Measures of Success

Determining measures of success is not as difficult as it may seem—but it is dependent upon setting clear objectives for the ad campaign. It is highly likely that different campaigns will have different objectives and hence unique yardsticks by which their success can be measured. Oftentimes, these campaigns will be conducted simultaneously and can be evaluated according to separate timelines which can range from weeks to years. Just as a “one size fits all” campaign is rarely effective in a diverse market like life science, so too should uniform measures of success be avoided. Each ad is intended to achieve a specific set of objectives and should be judged accordingly.

An ad’s purpose should be derived from the company’s overall positioning, marketing and sales strategies and the priorities set within each of these different plans. While every company is unique, advertising budgets are quite often determined only on the basis of what remains after other important initiatives have been funded. To ensure that advertising fully supports corporate objectives, a more disciplined, rational approach is needed.

Most leading life science vendors are positioned as “customer-driven” rather than “product driven” companies. It wasn’t always this way – it involved companies learning to respond to customer needs—from new products to post-sale support—rather than to develop innovative technologies for which no clear application had yet been identified. This transformation reflected the maturity of the life science tools industry. The next step in this continuing evolution now requires that a company’s advertising messages be aligned with the customer-facing operations in a way that helps to shape the customer’s perceptions, expectations, needs and purchasing activities. To do this, companies must adopt business practices that embrace a consistent, shared approach to systematically thinking through the complex dynamics of building a brand while promoting short-term sales goals.

Developing a Targeted Campaign

In general, ads will be used to support either a “sales-centric” or “brand-centric” objective. The target of a sales-centric advertising campaign is usually the end-user, lab manager or purchasing agent who has a current product need and will respond to an effective message by placing an order. The same individuals are also the targets of a brand-centric campaign, however, they do not have a current need but it is hoped that the ad message will be remembered when a need arises.

Both sales-centric and brand-centric campaigns will involve some combination of the following objectives:

- Generate awareness of the product or service and familiarize existing and potential customers with either performance characteristics (e.g., speed, reliability, etc.) or brand attributes (e.g., innovation, trust, market leadership, etc.);

- Encourage those exposed to the advertiser’s message to think about and consider the company or product’s strengths;

- Create and solidify brand preference by stressing its values to existing customers so they will recommend the company or product to their colleagues;

- Favorably influence and prompt purchase decisions.

In many cases, the corporate brand or the value proposition of a product tends to be driven by how management wishes it to be perceived, rather than by an understanding of the relationship between positioning, the resulting perceptions of the customers and the effect of the message on the purchasing behavior of distinct market segments. This is the point where many campaigns falter. In an effort to stretch the advertising budget to the maximum extent possible, objectives are merged and the clarity of the resulting message is diluted.

When attempting to accomplish too much at once, the message not only become diluted, but subsequent decisions reflect the uncertainty of the company’s objectives. Ad copy can become overly long and complex, design and layout loses focus and the list of websites and publications in which the ad is to appear gets broader—all in the hope that some part of the message will appeal to somebody, somewhere.

With advertising research, companies can avoid this situation through targeted advertising—delivering the right message to specific customers by means of the most appropriate medium. In so doing, the company ties its advertising message to a specific segment of the market in a way designed to support its strategic positioning and tactical sales goals for the segment.

Example of BioInformatics Inc.’s Quantitative Approach To Ad Testing

In formulating their marketing plans and in organizing direct sales, life science vendors often ask us to help them understand market segmentation – clearly defined groups of customers with similar needs to determine the appropriate marketing mix. When segmentation is used specifically to support advertising strategy, setting clear objectives for the ad becomes easier and measuring the success of the ad becomes possible.

Segmentation in Support of Advertising

Due to the diversity of the life sciences market, vendors often face extraordinary challenges in identifying and segmenting their customers. In general, the customers of life science products are drawn from two very different segments:

- Institutional customers who have administrative responsibility for making purchase decisions. At the highest level, senior purchasing managers of universities, pharmaceutical companies and government research facilities will fall into this group. Institutional customers also include department heads, departmental purchasing specialists, storeroom managers and others that must take into account financial considerations that go beyond the performance attributes of a particular product.

- End-users who are responsible for incorporating the product into their research. This group includes principal investigators, lab managers, staff scientists and research assistants who play a critical role in determining the effectiveness of the product and its ultimate success in the market. Although the influence of end-users is still significant, their influence over major sourcing agreements and purchase decisions is significantly less than what they exercise in their personal lives.

Detailed demographics for institutional customers (e.g., academic, industrial, government, etc.), and end-users (scientific discipline, applications, etc.) provide the groundwork for setting clear objectives for an advertising campaign. To be truly effective, however, it is also necessary to understand the attitudinal and psychological dimensions of how scientists learn about products and product information.

Most life science companies practice some form of simple market segmentation based on demographics such as geographic location, type of account and area(s) of research. A more thorough approach to segmentation involves identifying the critical brand values or product attributes and their relative importance to the chosen segment. Advertising research supplemented by statistical techniques such as regression and conjoint analysis can be a valuable tool in this endeavor. The segment’s current perceptions of the brand or product also have to be measured and quantified. Once the critical attributes have been identified, realistic targets—based on past experience and actual product performance—can be set for improving perceptions or influencing buyer behavior.

Segmentation & Ad Placement

For advertising purposes, however, life science vendors must also consider grouping customers together based on their media habits: specifically, what websites and publications (yes, print is still important!) are read for what reasons. Triangulating traditional demographics with additional segmentation points (such as product needs) and shared reading preferences will yield smaller, much more sharply defined segments receptive to different forms of advertising.

People are often judged by those with whom they associate. The same tenet holds true for companies that advertise in the life science market. There are literally thousands of scientific websites and publications where a company can place its advertisements. Not all advertising venues, however, are created equal. Even a cursory examination of the most popular scientific websites, journals and trade publications vying for the scientific community’s attention reveals differences in focus, quality, depth and relevance to individual areas of research.

Scientists—to a far greater extent than the average consumer—are keenly aware of these qualitative differences. As professionals, their personal success is often measured by where, and by how frequently, their research is published. Moreover, they rely upon the information contained within scientific publications as a key foundation for achieving their professional goals. Scientists can also be unforgiving. A publication that fails to meet their expectations is rarely afforded a second opportunity to redeem itself. There is simply too much to read and too little time.

Traditionally, the best place to advertise is where potential customers congregate. Today, life science advertisers have more choices than ever before. Publishers are launching new websites, new titles, enhancing their content and changing their format to attract a body of well-defined, loyal readers in an effort to attract advertising dollars. The value of a publication, however, is in the “eye of the beholder” or in this case, the scientific customer. Ultimately, the most successful publications, and therefore the most effective advertising venues, will be those that provide the greatest value to their readers. To effectively execute a targeted advertising campaign, it is essential that life science vendors be discriminating in their placement decisions.

Designing Ads for a Targeted Campaign

Ad design is a critical phase in the development of an effective campaign. Advertising designers must have an excellent grasp of the ad’s objective. In life science advertising, the balance between content and product concept is critical. It has been a long held belief that scientists respond only to ads with a high degree of technical content. Yet, the almost subliminal impact of creative ads should not be underestimated—too much technical content can be intimidating or confusing. The art of advertising is, of course, to blend a wide variety of elements that include text, images, color, size, readability and formats.

If all consumers are skeptical of advertising, scientists are even more so. Scientists are highly educated, analytical individuals who by the nature of their training and work also tend to be very skeptical. The “skeptic factor” cannot be overlooked when designing ads for this market. In one of our recent surveys on advertising, only 20% of scientists strongly agreed with the statement that “I feel like I can trust life science ads.” Ads should be straightforward and clear.

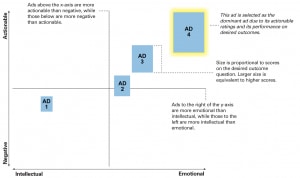

Finally, there is a tendency for key decisions in the development of an ad campaign to be based only on subjective judgments. Ad copy should be tested using advertising research to measure an ad’s ability to attract attention and break through the “noise.” Most ad testing uses quantitative measurements such as recall and recognition. Recall and recognition scores, however, are inappropriate when the aim of the ad is to change the customer’s perceptions. Because an ad is widely remembered and recognized by customers does not mean it will actually succeed in changing their perceptions of the product being advertised.

Conclusion

A systematic approach to targeted advertising can be put in place in most product categories once the dynamics of customer behavior are adequately understood through advertising research. When a vendor targets a well-defined market segment, it becomes easier to identify the targeted customer’s reading preferences, develop ads that address the segment’s unique needs, place them in the appropriate websites and publications and continuously measure their impact by means of changing perceptions or increased inbound leads. If perceptions and attitudes toward the vendor fail to change, or if inquiries fail to convert to new business at the expected rate, it is more likely that there is a problem with the company and its products than with the advertising.

Digital technology and the desire for greater efficiency and accountability is driving life science marketers toward more targeted advertising. The organizational changes required to implement an accountable advertising campaign have an added benefit—companies who do so will gain competitive advantage not only through more effective ads, but also through an improved and greater understanding of their customers.